The United States has faced grid emergencies before and emerged from them stronger by focusing on thoughtful solutions that aligned the incentives of consumers with suppliers. In the 1950s, the spread of electrified homes, factories, and air conditioning gave rise to a specter of blackouts and power shortages. In 1951, President Truman was forced to warn Americans that “the supply [of electricity] is expected to become increasingly short throughout the country.” Today, swap out Frigidaires for server racks and the story is the same: AI data centers are supposedly about to break the grid and bankrupt everyone within a 100-mile radius. Environmental groups are calling for moratoria on new facilities, citing rising bills and grid strain, and local opposition is hardening in the places where hyperscalers want to build. In this current debate, these opposition groups disregard the historical record of the 1950s, when innovation and modernization expanded supply and lowered energy costs for consumers.

Historical Context: The 1950s Electricity Boom

The similarities to this era run deeper than our fears. In the 1950s, U.S. electric capacity grew at 9.5 percent a year as homes filled with new appliances and air conditioning, and as rural electrification finally neared completion. According to a recent national load-growth assessment, U.S. energy use on the grid is now forecast to grow roughly 5.7 percent annually over the next five years, driven by data centers, new manufacturing, and electrification. To us, after a decade of “flat” demand, that kind of growth feels like a shock. Placed in historical context, it is a return to normal.

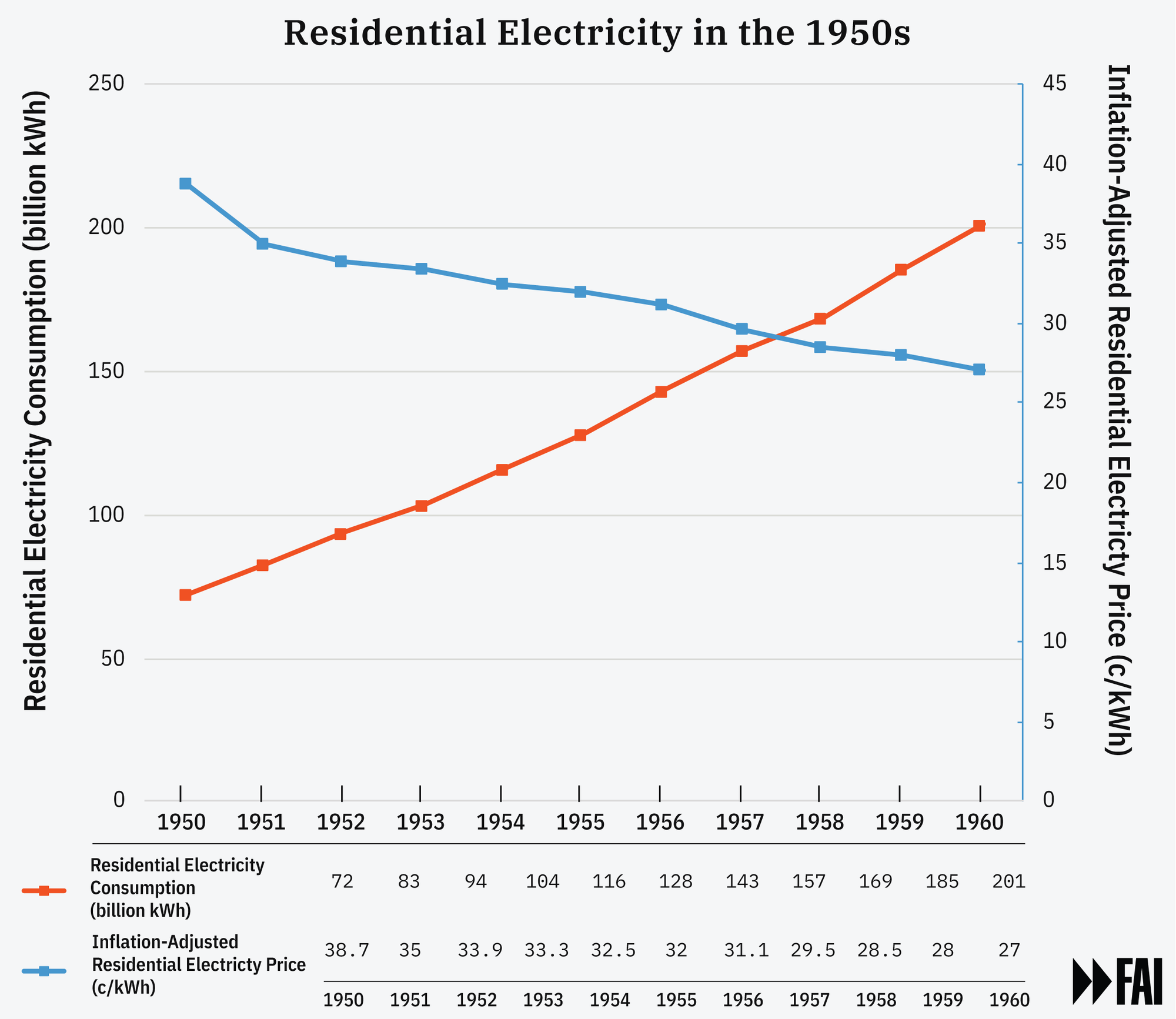

What’s most surprising is what happened to prices in the 1950s. During the mid-century appliance and AC boom, electricity didn’t suddenly become a rare luxury good. Instead, it became cheap mass infrastructure. Generation in the 1950s grew more than 8 percent a year, capacity nearly 10 percent, and utilities added plants and wires at a staggering clip. At the same time, coal and large hydro provided very low fuel costs, thermal efficiencies improved, and regulated utilities were allowed to earn a return on heavy capital spending as long as they passed on those savings to ratepayers. In real terms, the price of electricity kept falling across the 20th century, including the 1950s. Americans ended the decade using far more electricity at lower prices than they began it.

There were strains along the way. Regions that underbuilt capacity saw brownouts as AC adoption pushed summer peaks higher than planners expected. But the national story is clear: when policy let supply race ahead of demand, the result was abundance and falling real prices rather than permanent scarcity.

Opportunity: The Anchor of a More Affordable Grid

Today’s data center boom gives us a similar opportunity. Data centers are already around 4 percent of U.S. electricity use and could more than double their consumption by 2030. If we respond to the boom as a reason to build and scale the technologies of the future, we can turn data centers into the anchors of a much bigger, cheaper grid. But if we instead let that load hit a static grid, the pessimists will be proven right: congestion rents will spike, local wholesale prices will jump, and residential customers will end up subsidizing badly planned AI campuses.

To get there, we’ll need to make thoughtful policy choices. We’ll need to clear the permitting logjam for transmission and new generation, so projects can be approved in months, not decades. We’ll need to encourage firm capacity—nuclear, geothermal, and gas—alongside substantial additions of solar and storage, so the grid can support the growing load without leaning on scarcity pricing. We’ll need to write interconnection and tariff rules, so large customers fairly pay for the upgrades they require (or perhaps bring their own generation), instead of quietly socializing those costs onto everyone else’s bill.

Conclusion

The 1950s electricity boom did not break the American grid. It forced the country to build a modern one. Today’s data center boom offers the same kind of test. With bad policy, we’ll get higher bills and rolling brownouts. With good policy, we’ll get something closer to the 1950s outcome: rapidly rising electricity use and falling real prices for all Americans.