Our Lead in AI Is Fragile

The US currently has a lead in AI across chip design, data center build-outs, software tooling, fundamental research, and the production of the best frontier models. However, this lead is fragile.

Chinese firms are rapidly innovating at the technological frontier. At the model layer, DeepSeek R1, Alibaba’s Qwen 2.5 Max, and Tencent’s Hunyuan T1 are now competitive with the best frontier models from OpenAI and Anthropic. At the hardware layer, both Chinese startups such as DeepSeek and tech giants such as SenseTime are buying Huawei’s Ascend 910C chip, which reportedly delivers 60 percent of the performance of an NVIDIA H100 for crucial day-to-day inference tasks. At the application layer, Chinese firms have gone into a frenzy, deploying frontier AI across the value chain, from cars to air conditioners.

To counter this challenge, the United States has relied on export controls to protect its advantage at the frontier. Over the past three years, Chinese access to American AI computing hardware and models themselves has been progressively restricted. These export controls have had the dual effect of constraining China’s ability to produce its own chips and limiting its ability to purchase the most advanced Western AI chips. In turn, these efforts have been repeatedly circumvented by smuggling and front companies, prompting revisions. The culmination of these revisions over the past few years is the Diffusion Rule, which groups the world into three tiers: Tier I for the United States and 18 close allies; Tier III for competitors and adversaries such as China, Russia, and Iran; and Tier II for most other countries in the world. Through its Validated End User Program, the Diffusion Rule ensures American and allied firms remain the partner of choice for building data centers while incentivizing firms in Tier II countries to align with the American AI ecosystem and disentangle from the Chinese ecosystem to receive chips.

However, our advantage will not last forever. In the face of America’s export controls, China has launched a massive bid for self-sufficiency in chip manufacturing, with Beijing taking actions such as launching a $47.5 billion fund for the purpose in May 2024—the third in a series of the semiconductor “Big Fund.” Though self-sufficiency in advanced semiconductors will not happen this year or next, it is certainly possible—and some would say likely—that Chinese firms will eventually build an indigenous manufacturing supply chain producing a competitive volume of AI chips at some point in the future. Once this happens, Chinese firms’ experience reaping efficiency gains at the model layer, as seen in DeepSeek R1, alongside their technical talent, strong hardware manufacturing capacity, and large domestic market, will allow them to rapidly scale compute production, train better models, and build AI data centers across the world, outcompeting America and its allies. By capturing the global market, Chinese firms would reap enormous revenues and data to out-innovate American firms even further, handing China a significant advantage over the United States.

The United States and its allies have a closing window to win on AI. Export controls have bought the United States and its allies time to act to win over the global AI market while we still have advantages in both hardware and software. To complement these export controls, we need to run faster and build our innovation lead.

Therefore, we also need a strategy of “full-stack diffusion” that will durably embed American leadership in AI across the world and widen our gap ahead of China. That means promoting products across our AI stack in a nuanced and strategic manner, using a combination of financing, export controls, standards-setting, and other mechanisms.

Global Markets Determine Who Wins AI

Diffusion matters because it is a foundational pillar from which the benefits of AI for national power emerge. Economically, the nation whose firms win those global markets will accrue revenue to reinvest in algorithmic improvements and compute infrastructure that tip the balance of frontier innovation. Geopolitically, the nation whose chips and models become the platform for the rest of the world’s applications will wield significant leverage such as the United States currently wields in cloud computing. Culturally, the nation whose AI applications become the next Instagram or TikTok will supercharge its soft power on a scale that could make social media look small.

Furthermore, there are persistent first-mover advantages across the AI stack. Certain parts of the AI stack are very durable, as they have high switching costs and require updates infrequently. These exports include AI data centers, software used by government entities worldwide, and more. Whoever is the first to sell these durable parts of the stack will fill a customer need that may not come again for years—becoming the long-term foundation upon which other nations’ AI ecosystems are built. Moreover, these durable AI products confer a number of additional benefits. They can be platforms upon which other American or Chinese AI products can be introduced. They confer persistent advantages through data moats and network effects. And through the AI ecosystems they build, they can make other hardware and software layers of the stack more durable than they would be otherwise.

China has long understood the lesson that global deployment matters. From telecommunications equipment to solar panels to batteries to electric vehicles, the United States has repeatedly pioneered the development of transformative technologies, but it is China that has dominated its global deployment. Today, Chinese electric vehicles account for 76 percent of the global market. Huawei and Honor smartphones now account for 17.6 percent of the global smartphone market—the world's second-largest brand. With each global deployment of new technology comes a durable advantage because the costs of switching are so high—for example, when the UK banned Huawei 5G equipment in 2020, the move cost $650 million and will require seven years to finish implementing.

In turn, some attribute China’s previous successes in global deployment to unfair market practices or intellectual property theft. While those factors matter, it would be a mistake to ignore China’s fundamentally impressive strengths in technology, including a well-educated scientific workforce, generous state support for both basic research and commercialization and crucially in this context, effective state-led global diffusion policies that build markets for Chinese firms. In green technologies, the Export-Import Bank of China provided Y81 billion in loans to three Chinese firms, while state-run Sinosure helped provide insurance for a €216 million electric vehicle battery gigafactory in Douai, France. This support is not limited to hard financing. In telecommunications, for example, Huawei began holding 5G training for officials in Saudi Arabia as early as 2019. These efforts even extended to the diplomatic realm, where Beijing has prioritized recruiting embassy staff with knowledge of EVs to support their export promotion abroad. Together, Beijing’s state-led strategy for diffusion has allowed it to dominate the global deployment of new technologies time and time again.

China is now well positioned to repeat this effort in AI. Years of successful state-led digital promotion efforts, such as the Digital Silk Road—in which China invested over $79 billion between 2015 and 2019 to promote technological exports abroad—have given the Chinese state a tried-and-tested playbook to follow. Software applications like the “smart city” systems Chinese firms have sold to over 100 countries also give firms a natural platform upon which to introduce their AI applications worldwide. Meanwhile, Chinese companies are now also developing customized models for low-resource languages across emerging global markets, while Beijing runs vocational AI classes in over two dozen developing countries and strikes deals for scientific exchanges that facilitate technological transfer.

Export controls stand in the way of Chinese dominance in AI—for now. Export controls prevent Chinese firms from making enough chips for their domestic needs, let alone building a flurry of AI-focused data centers in international markets. U.S. export controls have thus prevented China from securing the sort of durable position in the global AI market that they have successfully secured in other sectors. While Chinese firms build data centers in countries spanning from Egypt to Malaysia, many of these do not appear to be specialized for AI, helping ensure that American and allied firms remain competitive. However, if America and its allies do nothing to proactively promote our AI exports, the story of 5G and EVs will repeat, locking America out of the global market.

Where Is America?

While China is playing to win, we aren’t even showing up to compete. The U.S. is plagued by a dysfunctional, fragmented strategy for technology diffusion that hampers our national competitiveness in AI. Export policy lacks coordination among the key agencies: the Export-Import Bank (EXIM), the Development Financing Corporation (DFC), the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), among others. For instance, EXIM, which runs the China Transformational Exports Program (CTEP) with a bipartisan China competition mandate, does not have DFC’s equity authority that allows it to support deals not backed by physical assets.

EXIM, whose mission is to support American jobs through export promotion, has lost its global leadership position and faces significant structural disadvantages compared to Chinese institutions. EXIM is constrained in risk appetite by overly restrictive default rate caps that can halt all lending, and the 2024 EXIM competitiveness report found that it was rated as far less competitive than other export credit agencies. The report also rates it as “the worst” with respect to its overly burdensome U.S. content requirements. EXIM’s CTEP, whose mandate is to help exporters facing competition from China in critical technologies, is heavily underutilized, hampered by slow processing times, and under-resourced with fewer than four full-time staff. It also lacks a financing mechanism fit for software, given that few treat software as a long-term capital expenditure requiring debt financing, as EXIM often supports. Together, these facts mean that, of the transactions that EXIM has made, 88 percent of transactions ($1.5 billion) were in wireless and renewable technologies, while it made only five transactions on AI applications worth only $8 million, and there have been zero transactions for high-performance computing (HPC) infrastructure.

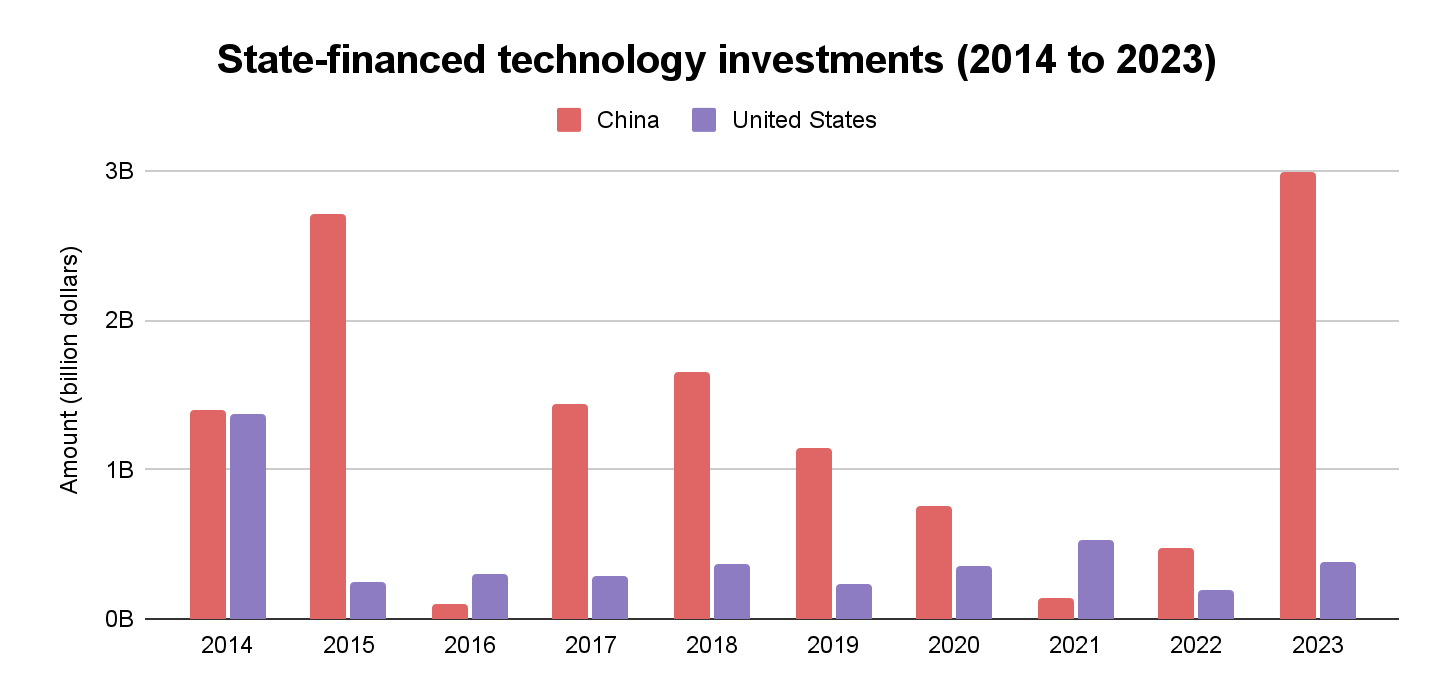

Other agencies suffer from similar shortfalls. Of the $27 billion in authorizations DFC has made since its creation in 2019, there has been only a single $300 million deal relating to computing infrastructure. While USTDA—which primarily offers technical assistance on development projects—has helped with smart city rollouts in India, Turkey, and Indonesia. But these efforts need to be significantly scaled up to compete with Chinese firms that have reached over 100 countries. Lastly, despite the importance of information technology for economic development, the MCC, an agency established to offer development grants to countries with “good governance” practices, does not have a sectoral focus on technology despite being clearly integral to global governance. This collectively dysfunctional ecosystem has strategic consequences: the value of state-supported technology deals from the U.S. has been one-third that of China (Figure 1).

Figure 1: China’s state-financed technology investments (organized around the Belt and Road Initiative) have dwarfed U.S. deals backed by the EXIM Bank and DFC over the past 10 years.

In turn, our lack of a strategy for full-stack diffusion has resulted in our companies going at this alone. American firms and workers are world leaders in AI. American companies such as OpenAI and Anthropic are developing the world’s best frontier AI systems, Amazon and Microsoft are the world’s largest cloud computing providers, and American startups in the “little tech” ecosystem drive new innovation. However, in key battleground states like Indonesia, the U.S. government has offered little to no support to our companies while they compete intensely with Huawei, Tencent, and Alibaba, which are directly supported by China’s Digital Silk Road engagement with the Indonesian government. In other markets, our companies have chosen to partner with regional powers to leverage their relationships to fill a gap that the U.S. government could have filled—as evidenced by Microsoft’s deal with the UAE’s G42 in Kenya to build AI infrastructure and local capacity in AI skills. And for startups that are looking to enter undersupplied export-friendly products like public sector software, support from the U.S. government to open up foreign markets is totally absent, leaving the field open for Chinese state-backed firms.

Our Closing Window to Win

The unique confluence of America’s leadership in innovation and well-timed export controls have given America and our allies a closing, last window of opportunity to win the global AI stack. We need a comprehensive, whole-of-government diffusion strategy that supports our innovators and workers. This regime must be based on three core tenets. First, it must be a full-stack strategy, simultaneously promoting American data center build outs while ensuring American and partner AI models run from those data centers to power American and partner applications. Second, it must be an attractive strategy, one that makes our products cheaper, higher quality, and more performant in diverse global markets so we are the partner of choice for the world. Third, it must be a durable strategy, one that captures first-mover advantages across the AI stack and ensures countries want to stay part of the American AI ecosystem.

Of course, we need strategic partnerships to supplement a unilateral full-stack diffusion strategy. America’s allies and partners have a vital role in a future strategy, whether by allied companies creating models to power American AI applications in numerous global languages or cooperating with firms like Nokia and Ericsson to make competitive counters to Chinese firms’ ecosystem-in-a-box offers. These need not be traditional partners either: a sustainable full-stack diffusion strategy will forge new relationships with firms and workers across emerging markets in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, folding these countries into the American AI ecosystem in a mutually beneficial manner. Building these kinds of relationships creates the ultimate form of durability for American AI products.

Furthermore, this full-stack diffusion strategy can be designed to complement our existing export controls. While many claim that export controls and diffusion are contradictory, well-designed export promotion can act as a ladder to incentivize countries to scale up the three tiers of the Diffusion Rule, making American AI infrastructure and applications more enticing to the rest of the world. As part of this ladder, a good full-stack diffusion strategy might also include ways to support countries in securing their AI infrastructure and preventing chip smuggling to other actors. In this way, a full-stack diffusion strategy can provide a positive incentive to support our companies and firms while maintaining the Diffusion Rule.

We sit at a critical moment. China is rapidly ramping up its domestic production capacity for AI chips and moving towards indigenization breakthroughs. We need to seize this last window to win to ensure that the world runs on our AI infrastructure and applications.

In the next part of this series for the Foundation for American Innovation, we will lay out the specifics of what a united, whole-of-government export promotion strategy should look like.

This article was written solely in the authors’ personal capacities.