An artificial general intelligence system is typically defined as an AI-system that can accomplish any cognitive task better than the best human. For looser definitions, some FAI scholars believe we already have artificial general intelligence (AGI) in the form of systems like Claude Code, although the vision of an AGI system acting as a fully reliable, drop-in remote worker is clearly still some ways away. The AI Futures Model forecasts fully automated AI coders by 2031, while the forecasting platform, Metaculus, dates the arrival of “strong AGI” at 2033. Other analysts argue we still need one or two more technical breakthroughs to achieve AGI, perhaps related to long-term memory and continual learning. Regardless, most top AI researchers and industry leaders now appear confident that these remaining hurdles will be solved within a decade, if not much sooner. How is the arrival of an AGI likely to affect the U.S. economy?

Today, there are many economic and social theorists tackling this question.[1] As far as I know, however, Ray Kurzweil is the first public intellectual of his generation to advance the notion that artificial intelligence and information technologies were going to lead to radical increases in economic activity.[2] Kurzweil was a prolific inventor and made notable contributions to optical character recognition, text-to-speech synthesis, and speech recognition.[3] Most important for our purposes is that he continues to be cited as a key influence on artificial intelligence entrepreneurs such as Dario Amodei, Sam Altman, and Elon Musk.

Kurzweil’s basic macroeconomic claim is that the path to a post-AGI future will lead to substantially above-trend income growth and longevity for most. This has substantial policy consequences. For instance: if real GDP growth is going to be in the triple digits starting in the late 2020s or even in the early 2030s, as Elon Musk has speculated, why worry about the national debt? I am not the first to raise these points. More than two decades ago, when grappling with the prospect of AGI, Arnold Kling wrote:

All of the concerns that economists raise about the middle of this century, such as the external debt of the U.S. economy (the cumulative trade deficit), the fiscal implications of Social Security and Medicare, or gloomy scenarios for global warming, will be trivialized by the sheer heights that economic wealth will have scaled by that time. … the mountain of debt that we fear we are accumulating now will seem like a molehill by 2040.

We are more than halfway through the period from 2005 to 2040. Does any of this feel true to you? In what follows, I will be examining several of Kurzweil’s key economic claims, what Arnold Kling once called “Kurzweilomics.”

Do You Still Believe in Kurzweilomics?

Kurzweil’s basic economic ideas in his magnum opus, The Singularity Is Near (2005 hardcover, 2007 paperback), run as follows:[4]

- Growth in labor productivity is the major determinant of income growth.[5]

- Growth in labor productivity arises primarily from technical improvement.[6]

- Since artificial intelligence research and development is a human activity, an AGI would definitionally be able to improve itself. As a result, technical improvements should accelerate over time.

Eventually, Kurzweil writes, “the pace of technological change will be so rapid, its impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed,” i.e., the singularity will have arrived. In the approach to that momentous occasion, acceleration of technical improvements should lead to an increase in the growth of income growth itself.

So far, so good. How much economic growth are we talking about here? Kurzweil himself is reticent to convert his predictions and ideas about productivity growth into quantitative real GDP growth forecasts in The Singularity Is Near.[7] However, in the January 2001 version of his essay “The Law of Accelerating Returns,” Kurzweil does advance a quantitative theory of how his ideas about technology translate into economic growth.[8] There, he wrote:

The economy “wants” to grow more than the 3.5% per year, which constitutes the current “speed limit” that the Federal Reserve bank and other policy makers have established as “safe,” meaning noninflationary. But in keeping with the law of accelerating returns, the economy is capable of “safely” establishing this level of growth in less than a year, implying a growth rate in an entire year of greater than 3.5%. Recently, the growth rate has exceeded 5%.

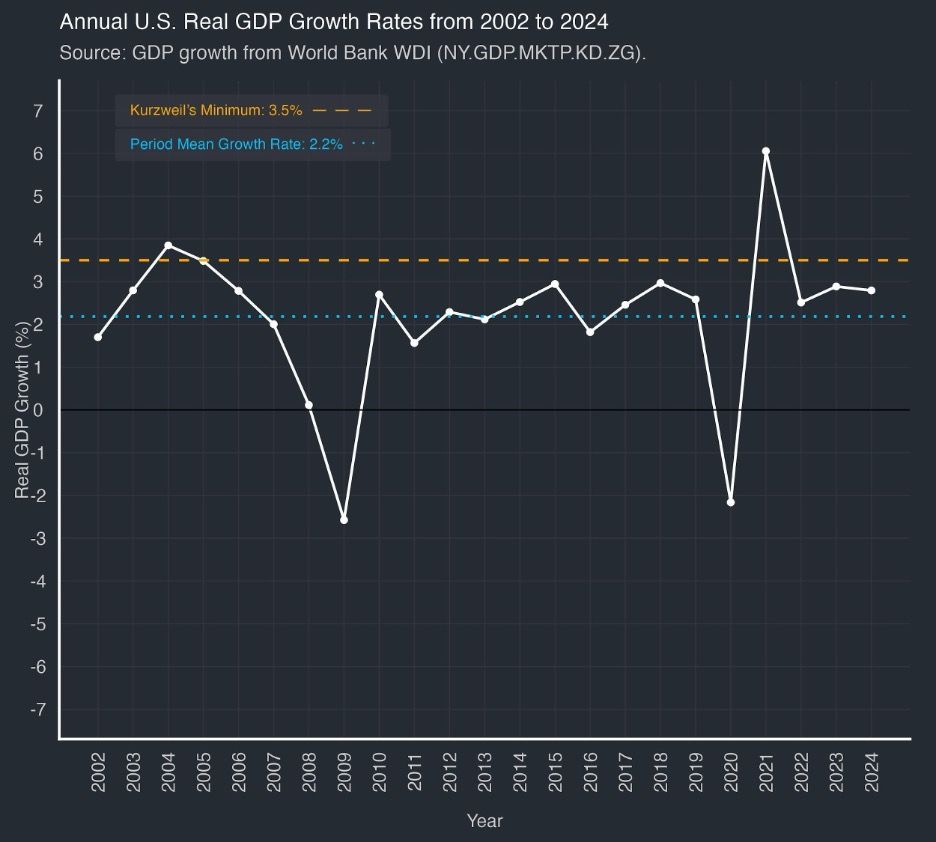

So, starting around 2002, if Kurzweil was correct, real GDP growth rates should have met or exceeded 3.5 percent. Below, I have plotted quarterly U.S. real GDP growth rates from 2002 to 2024.

It should now be clear why Kurzweil was reticent to make quantitative macroeconomic forecasts in his writing after The Singularity Is Near: real GDP growth rates in the U.S. followed trend growth rates with no obvious increase. Meanwhile, the only years in which real GDP growth rates exceeded 3.5 percent were 2004 and 2021. The former marks the start of the housing bubble (eventually leading to the Great Recession) while the latter marks a recovery from the COVID-19 recession the previous year. In other words, these years of high real GDP growth arose from regular macroeconomic fluctuations rather than the macroeconomic regime change anticipated by Kurzweil.[9] Kurzweil essentially conceded his forecasting difficulties in his 2024 book, The Singularity Is Nearer, where he wrote:

One sticking point in this thesis has been a productivity puzzle: if technological change really is starting to cause net job losses, classical economics predicts that there would be fewer hours worked for a given level of economic output. By definition, then, productivity would be markedly increasing. However, productivity growth as traditionally measured has actually slowed since the internet revolution in the 1990s. … This has been one of the great economic mysteries of the past decade. With information technology transforming business in so many ways, we’d expect to see much stronger productivity growth. Theories abound as to why we haven’t.

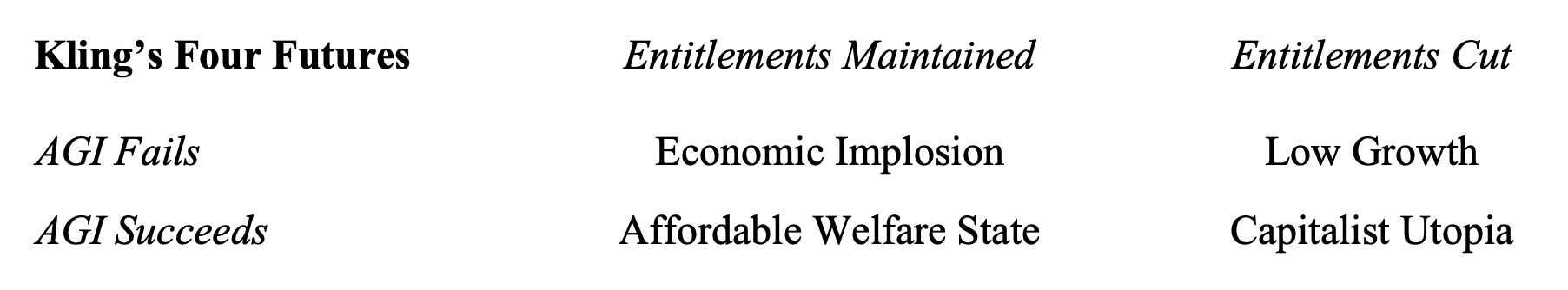

The most tantalizing aspect of AGI for macroeconomic policymakers is that it will enable the U.S. to kick the can down the road on America’s exploding entitlement costs, especially in Medicare. More than two decades ago, when grappling with these issues, Kling argued that the U.S. faced one of the following four futures (lightly modified from the original).

The scenarios in which AGI fails are simple enough. If AGI fails to materialize, then the current entitlement trajectory of the U.S. will result in an economic and political collapse. Even cuts to entitlements will result in relatively low growth for the foreseeable future because the primary expected driver of economic growth will simply not have panned out.

Conversely, entitlement cuts and the success of AGI will result in what Kling calls the “Capitalist Utopia” scenario. In this scenario, prudent households can easily self-finance retirement, including health costs, simply by saving from their high incomes. Households that are not prudent will engage in political conflict with prudent households and attempt to reinstate entitlements. Kling summarizes the “Affordable Welfare State” scenario in the bottom left cell of the table as follows: “If output per person in 2025 is more than 5 times what it is today, then the economy will have won the race [between entitlement growth and the growth of real economic activity]. … We will pay off this debt the way someone who wins a million-dollar lottery pays off a car loan.”[10]

So, which quadrant of the table are we in? Real GDP per capita in 2005 was about $44,000 in 2009 dollars. Today, it is about $70,000. At a glance, this would place us in one of the top two quadrants of Kling’s table, but Kurzweil rejects this interpretation outright. He maintains that we are on track to achieve AGI more or less on the time frame he originally proposed in The Singularity Is Near.[11] How does Kurzweil reconcile this proposition with the economic data? In The Singularity Is Nearer, Kurzweil presents his favored theory as follows:

If automation is really having such a huge impact, there appears to be several trillion dollars of the economy “missing.” In my view, which has been growing in acceptance among economists, much of the explanation is that we don’t count the exponentially increasing value of information products in GDP, many of which are free and represent categories of value that did not exist until recently. When MIT bought the IBM 7094 computer I used as an undergraduate for around $3.1 million in 1963, that counted for, well, $3.1 million ($30 million in 2023 dollars) in economic activity. A smartphone today is hundreds of thousands of times more powerful in terms of computation and communication and has myriad capabilities that did not exist at any price in 1965, yet it counts for only a few hundred dollars of economic activity, because that is what you paid for it.

Kurzweil essentially argues that any U.S. consumer with an iPhone is, in some sense, extraordinarily wealthy in 1965 terms—millionaires in all ways except for their checking accounts.[12] Maybe so. However, the problem for Kling’s original “Affordable Welfare State” scenario should become immediately apparent. If Kurzweil’s interpretation of the data is correct, then AGI will not appear in the form of GDP, nor will it solve the U.S.’s fiscal challenges. For AGI to address the U.S. fiscal cliff, it has to show up in the form of increased economic activity, as represented by taxable transactions, and greater conventionally measured labor productivity. People who maintain that we are near AGI and that it will solve the U.S.’s fiscal problems have the double burden of demonstrating both not only continued technical progress, but more critically, how that technical progress will yield increased conventionally measured labor productivity and willingness to pay for taxable services.

Kurzweil goes on to present a more satisfactory explanation for the failure of “technology” to appear in real GDP trends:

Even though such [digital] services are free to consumers, we can approximate people’s willingness to pay for them (also known as consumer surplus) by looking at their choices.For example, if you could earn $20 by mowing a neighbor’s lawn but choose to spend that time on TikTok instead, we can say that TikTok is giving you at least $20 of value. As Tim Worstall estimated in Forbes in 2015, Facebook’s US-based revenue was about $8 billion, which would thus be its official contribution to GDP. But if you value the amount of time people spend on Facebook even at minimum wage, the true benefit to consumers was around $230 billion. As of 2020 (the most recent year for which data is available as this book goes to press), US social media-using adults spent an average of thirty-five minutes each day on Facebook. With around 72 percent of America’s roughly 258 million adults using social media, this suggests $287 billion of economic value from Facebook that year, using Worstall’s methodology. And a 2019 global survey found that American internet users spent an average of two hours and three minutes per day on all social media – which contributed around $36.1 billion in advertising revenue to GDP but implies a total benefit to users of over $1 trillion per year.

In other words, most of the value of the new products enabled by the information technology revolution constitute a kind of consumer surplus. This line of thought is more satisfactory, not only in terms of conventional economic theory, but also because it yields testable predictions and, if true, has important policy implications.[13] Namely, if the path to AGI is generating enormous consumer surpluses, then more sophisticated consumer-differentiated pricing—e.g., surveillance pricing—would allow for that value to appear in GDP and reduce U.S. fiscal pressures.

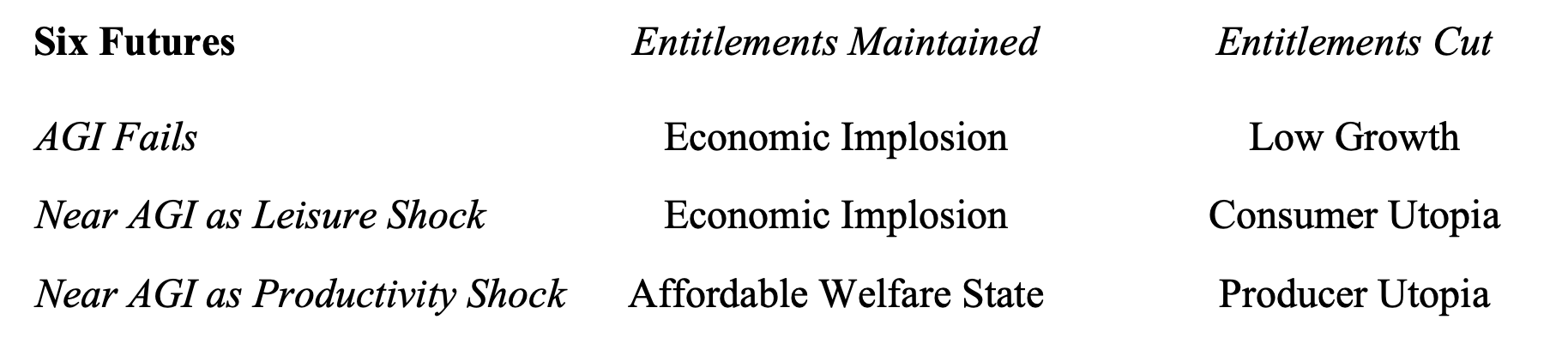

However, Kurzweil’s optimistic, productivity-focused interpretation of the relationship between improvements in computing power and labor market outcomes is not the only one that economists have proffered. An intriguing paper published by Aguiar et al. (2021) suggests that “video game and recreational computing” technology has undergone drastic improvements, reducing the labor supply of young men. It is not especially difficult to imagine a future in which the dominant effect of AGI-adjacent technologies, at least in the near term, is a “leisure shock” that draws potential workers out of the labor force at the expense of their own incomes, relationships, and future well-being. We might modify Kling’s matrix to add the following scenarios:

The AGI failure scenarios are essentially the same as in the first table. However, the modified table makes it clear that near-AGI technologies can be seen to have two effects. In the first scenario, AGI primarily appears in the form of a leisure shock. People spend more time in virtual worlds at the expense of activity that would be valued by others who are willing to pay them, i.e., productive work.[14] In this scenario, but for the exploding entitlement obligations of the U.S. government, consumer welfare would indeed dramatically increase. A sufficiently large entitlement cut would result in a “consumer utopia” in which labor productivity simply continues to increase at the trend rate, but the quality of entertainment and potential consumer surplus explodes. In some ways, this scenario is most similar to what Kurzweil hypothesizes is already happening: improvements in information technologies are creating new, extremely low cost consumer goods benefiting individual welfare in the economistic sense, but not appearing in GDP.

AGI-adjacent technologies will no doubt improve productivity in some ways—e.g., automating driving, preventing deaths, and enabling productive work into older ages. The size of these productivity-enhancing effects remains open to debate.[15] If the productivity-enhancing effects dominate, then we wind up in one of the bottom two cells of the modified matrix. Absent changes to the entitlement system, economic growth will increase relative to current levels and likely cover the cost of entitlements. This puts us back in the “Affordable Welfare State” scenario. In the producer utopia scenario, the returns to work substantially increase. Self-financed retirement for most is relatively easy. Political conflicts will occur between retired and near-retired workers in the current entitlement system, who will resist entitlement cuts, and those far from retirement, who will support entitlement cuts.

Forecasting U.S. Growth Rates: Elon Musk and Roon vs. an Undergraduate Economics Textbook Model

The powerful grip that Kurzweilomics has on technologists should be surprising in light of its predictive track record thus far. As we have noted, even if we concede the (highly contestable) fact that “technology” has progressed at exponential rates, technology adoption does not have any straightforward relationship with conventionally-measured labor productivity growth. Furthermore, technical improvements might well yield reductions in labor force participation and labor productivity via leisure shocks that depress output. If Kurzweil’s interpretation of how information technology impacted the economy from 2007 to 2024 is accurate, then there is no reason to believe that continued increases in “technology” as Kurzweil understands it will necessarily translate into greater economic growth or avert the U.S.’s coming fiscal crisis.

The basic issue with Kurzweilomics, from a statistical perspective, is that believers seem to assume that increases in total factor productivity—i.e., how much the economy produces given a fixed stock of capital and labor—is autonomous, with information technology simply “adding” to the trend. As Andrej Karpathy points out, AGI and its predecessors are more likely to be a major source of the trend in total factor productivity increases in our period and in the near future. Nonetheless, as Karpathy also argues, the logic of Kurzweil’s singularity is compelling. At some point, one of the descendants of today’s LLM-technologies will prove capable of changing its own code, perhaps to make itself more computationally efficient in some sense. If such improvements could be reliably sustained, then Kurzweil’s singularity would soon follow.

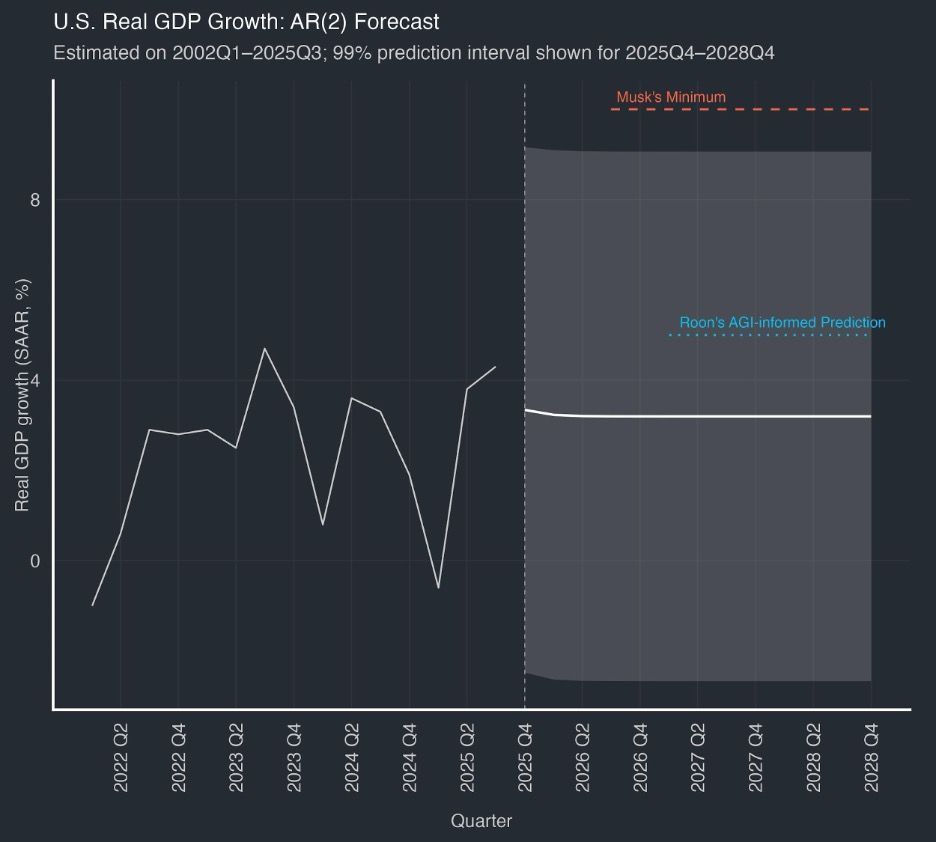

Are we there yet? Quarterly growth rates in the Trump administration have mostly exceeded Kurzweil’s 3.5 percent minimum.[16] Kurzweil fan and richest man in human history Elon Musk has gone as far as to forecast “double-digit economic growth is coming within 12 to 18 months … triple-digit is possible within ~5 years.” A more sober forecast comes from OpenAI employee Roon, who guesses that U.S. real GDP growth will exceed 5 percent in 2027.[17] One can say that if the current artificial intelligence technology is similar to historical technical shocks, then one would anticipate no deviation from trend economic growth, i.e., the Karpathy prediction.[18]

In an effort to evaluate the credibility of these predictions, I downloaded the quarterly real GDP growth time series from 2020 Q4 through 2025 and fit a minimal time series model from the classic undergraduate econometrics textbook Introduction to Econometrics, by James Stock and Mark Watson.[19] I then estimated 99 percent prediction intervals for real GDP growth for 2025’s fourth quarter and the eight quarters spanning 2026 and 2027. The prediction is given by the solid line starting with the fourth quarter of 2025, which has not yet been released. The upper and lower bands provide the 99 percent prediction interval. Finding a value outside of the 99 percent prediction interval would occur in fewer than 1 of 100 cases if the model was correct. I have also plotted the minimum quarterly growth that would be consistent with Elon Musk’s forecast and Roon’s AGI-informed 2027 forecast.

As you can see, even one quarter of 10 percent growth would be well out of the range of trend growth rates. The materialization of such a datapoint would be compelling evidence against the trend model, and a point in favor of alternative hypotheses—e.g., if not the rapid recovery from a financial crisis, war, or epidemic, then the dawn of productivity-dominant AGI. On the other hand, a quarter with 5 percent or more annualized growth would not be out of the range of the U.S.’s macroeconomic experience. The flipside of this observation is that the materialization of Roon’s prediction of, say, 5.1 percent quarterly annualized growth in 2027 would also not provide evidence that we have entered a new macroeconomic growth regime.

In short, Kurzweil’s economic ideas are not a credible reason to ignore the U.S.’s unsustainable fiscal position. The value created by AGI may follow prior digital technologies in being largely captured by consumers in the form of cheaper goods and services, rather than through radically higher—and taxable—economic outputs. This would still generate increased economic welfare, enabling a consumer utopia of sorts if entitlement cuts materialize. Conversely, if AGI drives real labor productivity and GDP growth, we may as yet be able to have our entitlement cake and eat it, too. However, absent any data putting U.S. GDP growth substantially above its recent historical trend, it is premature to risk a fiscal crisis on a technological deus ex machina. The balance of these trends leads me to advance the currently radical hypothesis that the median American will experience a modest rather than transformative improvement in their quality of life, at least as measured through real GDP per capita, through, say, 2035.[20]

[1] In future work, I hope to address some of their ideas.

[2] Of course, earlier writers developed similar notions implicitly—e.g., Kurt Vonnegut in Player Piano, and H.G. Wells in World Brain.

[3] Indeed, both The Singularity Is Near and The Singularity Is Nearer acknowledge a laundry list of collaborators from the hard sciences and business world, but, as far as I can tell, not a single economist.

[4] The “microfoundations” of Kurzweilomics are a little mysterious. As best as I can tell, they consist of two propositions. First, technical improvement growth rates can successfully be forecast ex ante. Kurzweil makes much of the fact that analysts tend to linearly extrapolate technical improvements when they should be using an alternative “exponential” model. Second, there is a straightforward mapping from the adoption and improvement of various technologies to productivity. Although both propositions are problematic, I would argue that the second proposition is especially shaky. The most basic objection is that many new technologies appear to harm short-term labor productivity.

[5] A challenge is that growth of what—labor productivity, GDP, or GDP per capita—tends to be left ambiguous in Kurzweil’s framework. For now, I will focus on GDP.

[6] If technological improvements are thought to include organizational and institutional changes, then this is undeniably correct. Setting this caveat aside, it is notoriously difficult to connect technical changes to consequent labor productivity changes. There is a considerable literature on the “Solow paradox”—the fact that information technologies developed in the 1970s and 1980s appeared to have little impact on GDP trends until the 1990s at the earliest.

[7] The Singularity Is Near simply relayed the elevated global growth rate forecasts by the World Bank, which were notably increased by China and India’s catch-up growth. High catch-up growth in developing-country economies says little about the validity of his macroeconomic ideas. After The Singularity Is Near, I am not aware of any growth rate forecasts by Kurzweil.

[8] Kurzweil omitted the key paragraph in subsequent reprintings of the essay.

[9] Intriguingly, in the 2001 essay, Kurzweil continued:

None of this means that cycles of recession will disappear immediately. The economy still has some of the underlying dynamics that historically have caused cycles of recession, specifically excessive commitments such as capital-intensive projects and the overstocking of inventories. However, the rapid dissemination of information, sophisticated forms of online procurement, and increasingly transparent markets in all industries have diminished the impact of this cycle. So “recessions” are likely to be shallow and short lived. The underlying long-term growth rate will continue at a double exponential rate.

As the plot shows, about seven years later, the U.S. would face the deepest recession recorded since the Great Depression. The recession would be exceptionally long compared to the 1980, 1982, 1991, and 2000 recessions.

[10] The essay and blog AI 2027 helpfully summarizes what a delayed variant of this scenario might look like.

[11] Kling remains ambivalent about whether we are on the path to AGI.

[12] A more natural explanation for the failure of massively increased computer power is simply diminishing marginal utility of computing and hence lower willingness to pay for the next 10x technical improvement.

[13] N.B., I do not believe that this approach to measuring consumer surplus is taken seriously by academic or public-sector economists, but it might still be useful for a back-of-the-envelope calculation.

[14] If AGI is used to enhance other leisure activities—e.g., to find the best movies, make even better and more addictive video games, or discover new running trails—this could safely be grouped with the aforementioned “leisure shock” scenarios.

[15] Anecdotally, I know of at least one company that has completely stopped hiring via the use of artificial intelligence technology while continuing to grow its profits and, presumably, output at the same rate that its founders expected. This would be an example of labor productivity-enhancing technical change.

[16] Some have pointed out that much of this growth is in health care. For complex reasons, this is not a decisive point against the singularity hypothesis. Rich societies spend disproportionately more on health care. The (assumed rational) expectation of greater earnings via coming technological improvements would also be expected to yield large present-day expenditures on health.

[17] This was revealed to me in an X DM.

[18] There are also formal tests for whether the U.S. economy is approaching a singularity that I hope to discuss in future posts.

[19] The model is an AR(2) following equation 15.11 in Stock and Watson (2019). Model selection would have yielded an AR(0). I start the data in 2020’s fourth quarter to exclude the COVID-19 recession.

[20] I picked 2035 with the general intuition that economic forecasts more than 10 years out (or demographic forecasts more than 30 years out) are more akin to hard science fiction than science.