How did a species of hairless primates stumble into technological civilization? And what does that say about where AI could be taking us?

The human brain is a neural network that evolved through blind optimization, so the fact that we learned to hack our own reward system and survive far outside our evolutionary niche at least give precedence to the risk of advanced AI going rogue. Going rogue is our everyday lived experience! It follows that one way to shed light on the AI alignment problem is to deepen our own self-understanding. Futurism via historicism.

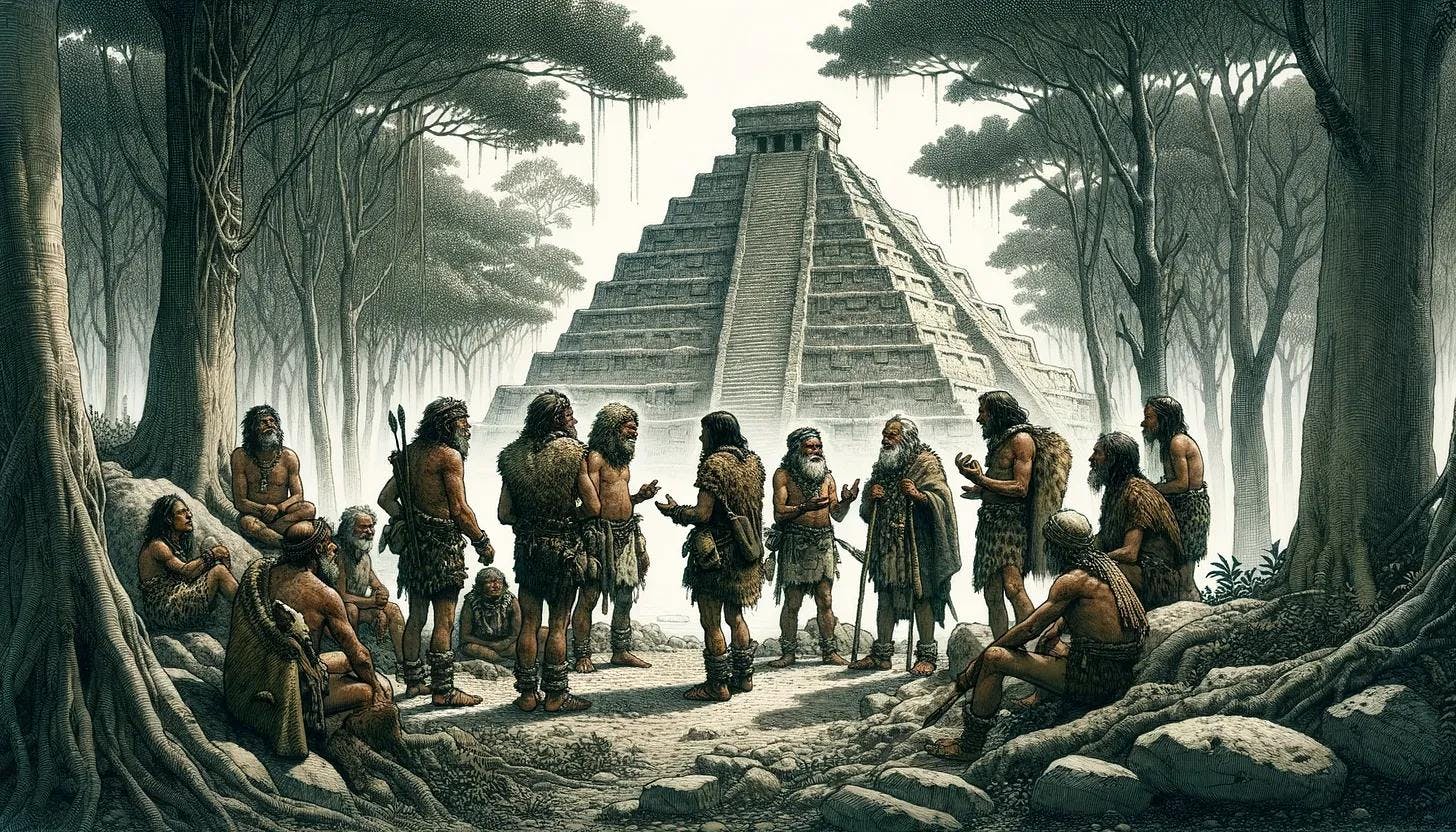

And indeed, for most of the last 300,000 years, humans lived in small bands of hunter-gathers, struggling to accumulate knowledge through oral tradition and ritual. Religion was largely animistic, with no distinction between the symbolic and natural orders. In a sense, there was no history: no record of what came before, no process to unfold the world to come.

What changed some 10,000 years ago to let us suddenly transcend these lowly origins and build the first truly complex societies? A lucky genetic mutation, divine intervention, ancient aliens? While recent archeological discoveries suggest human civilization is much older than we ever realized, there is still no consensus on this fundamental question.

In the beginning…

My money is on the theory put forward by Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson, who argue that human ultrasociality “arose by adding a cultural system of inheritance to a genetic one.” Genes and culture coevolved with the evolution of language as a medium for social learning, implying that nature and nurture are deeply intertwined. The key difference is that the reward function guiding social learning must be trained and retrained with each generation, and applies to entire populations rather than individual organisms or genes. This makes Boyd and Richerson’s theory distinct from a theory of “group selection,” as natural selection still takes a gene’s eye view. Nonetheless, cultural transmission “participates in [the] ultimate causation” of human behavior by providing the basis for scaled-up systems of cooperation.

As a modality for social learning, language evolved as a way to express imperatives, justify our actions to one another, and infer whether a reason is compatible with our shared commitments. Language is thus inherently normative — a way for small groups to institute and coordinate around mutually recognized rules and statuses. This is why norms and reasons alike have motivational oomph. To do your duty or to be persuaded by reason are both to feel “the unforced force of the better argument”; to be pulled in a certain direction by your normative control system. Language thus co-evolved with normative control to enable social integration and coordination, while the recognitive nature of norms reflects their endogeneity to the interactions of agents within a multi-agent game.

Our capacity for normative control seems to emanate in part from our System 2 — the slower, metacognitive process we employ when we plan ahead, reflect on our actions, evaluate counterfactuals, exercise self-control, and justify our behavior to our peers. Discursive reasoning abilities likely weren’t a de novo adaptation, but had to piggy-back on this basic inferential toolkit; what cognitive psychologists call “pragmatic reasoning schemas.”

Reason’s normative inheritance is manifest in the way we argue over factual matters as if they had deontological significance. For example, just as norms are expressed in terms of what’s permissible, prohibited or obligatory, epistemological statuses are expressed in terms of what’s possible, impossible, or necessary. As Joseph Heath argues in Following the Rules, this symmetry reflects how both serve to constrain or prune our practical actions and commitments. In turn, we tend to perform better on tests of abstract logical reasoning when the problems are reformulated into deontic rather than indicative terms, i.e. in terms of the conditions that would need to obtain to permit an action. We even tend to assimilate to the beliefs of our in-group as if truth were a function of socialization, giving rise to intellectual zeitgeists and calls to “read the room.” Social learning and our innate tendency to conform to norms thus gave rise to stable social conventions and cultures, while the role of language in reproducing those norms exerted a rationalizing bias on culture overtime.

The Extended Mind

Civilization thus kicked off with development of the original Large Language Model: formal writing systems. History had begun, thanks not merely to the advent of techniques to record events, but because the connections between events could now be situated in a logical historical progression. Without written language and norms, history would likely never have gotten off the ground, as the purely biological explanations of human sociality (kin-selection and reciprocal altruism) simply don’t scale. A symbolic medium for communication, in contrast, was just the sort of external scaffolding we needed to leverage our fleeting capacity for reason and agency into something greater than the sum of its parts — an example of what philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers call “the extended mind.”

Evidence of the extended mind is all around us, from the road markings we rely on for directions, to the way we use checklists to augment our working memory. As Clark puts it, language represents an “external artifact whose current adaptive value is partially constituted by its role in re-shaping the kinds of computational space that our biological brains must negotiate in order to solve certain types of problems, or to carry out certain complex projects.” Norms and culture work similarly, providing rules and social scripts that let us offload burdensome cognitive processes onto the external environment. This includes what Joseph Heath and Joel Anderson call “volitional prosthetics” — social technologies for aligning our higher-order preferences and promoting the exercise of self-control — suggesting “the extended mind” might as well be called “the extended will.”

The advent of writing systems thus created a medium for reason and agency to be embedded into objective institutions, giving logos a life of its own. Or as John 1:1 put it, “In the beginning was the Word,” and with history, “the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us.” With the residual stream of a coherent culture, ideas, tools and practical know-how could now be accumulated and refined across generations, building on what came before through the interplay of discursive and practical reason. This induced a continuity between stages of social development and thus a notion of path dependency — the main prerequisite for history to be more than “one damn thing after another.”

The historical process could then be studied, letting us make explicit what began as merely implicit in antecedent actions; to interpretively “read reason into” the structure of social practices or sequence of historical events. This can be seen in how the Torah interweaves its exhortations to follow the Deuteronomic Code with historical allusions to the moral and religious purposes they subserve. That is, the bible doesn’t merely issue commandments, but situates those commandments in stories that make their function deducible from the pragmatic context.

Reason can be embedded in practical norms or through various systems — militaries, markets, legal orders, bureaucracies — that steer and instrumentalize human action through explicit rules, commands and incentive structures. The reason latent in these social technologies necessarily transcends any individual reason giver. The birth of civilization was thus the birth of a kind of decentralized, cybernetic meta-agency, in which individual motives and actions became controllable inputs toward the “goals” of the collective. Monotheistic religions arose to mediate this spontaneous order by aligning individual commitments to the as-if agency of whole nations. Kings and pharaohs were just as much part of the “system” as the lowliest serf or peasant, selected for traits conducive to societal flourishing and the maintenance of order, now conveniently modeled as the will of God.

Scale is all you need

The seemingly sudden emergence of civilization around 10,000 years ago thus wasn’t due to a discrete evolutionary adaptation. Darwinian selection is gradual, and even theories of punctuated equilibria don’t operate on such short time scales. Rather, civilization took off because our norm-governed language faculty inadvertently gave rise to a process of cultural accumulation and refinement, as if the reason latent in discursive practices became a software layer hovering over society. This was essential, not only because cultures evolve much faster than genetics, but because it created a domain for new critical phenomena — cultural phase transitions — as society grew in scale and complexity.

In the case of the earliest human settlements, the gradual accumulation of agricultural knowledge eventually gave way to a demographic boom, inducing a division of labor and growing social complexity that went critical with the Neolithic Revolution. In the span of a few thousand years, the typical human transitioned from being a nomadic hunter-gather in a kin-based society organized around norms and customs, to being a farmer in a populous society organized around impersonal rules and hierarchies.

Like many physical phase transitions, there was no “going back” on the Neolithic Revolution; no way to “unring the bell.” While the median person’s quality of life in some ways regressed, the social dynamics favoring agriculture were self-reinforcing. Agricultural surpluses led to growing populations, enabling larger scale social organizations for collective action, more specialization, trade and product innovation, and even greater output. Humankind was thus irreversibly pulled into a new equilibrium, assimilating the remnants of hunter-gatherer society along the way.

The rest, so to speak, is history.